Someone Like Me: Young Coloradans share their stories of crisis and recovery

Young Coloradans share their stories of crisis and recovery

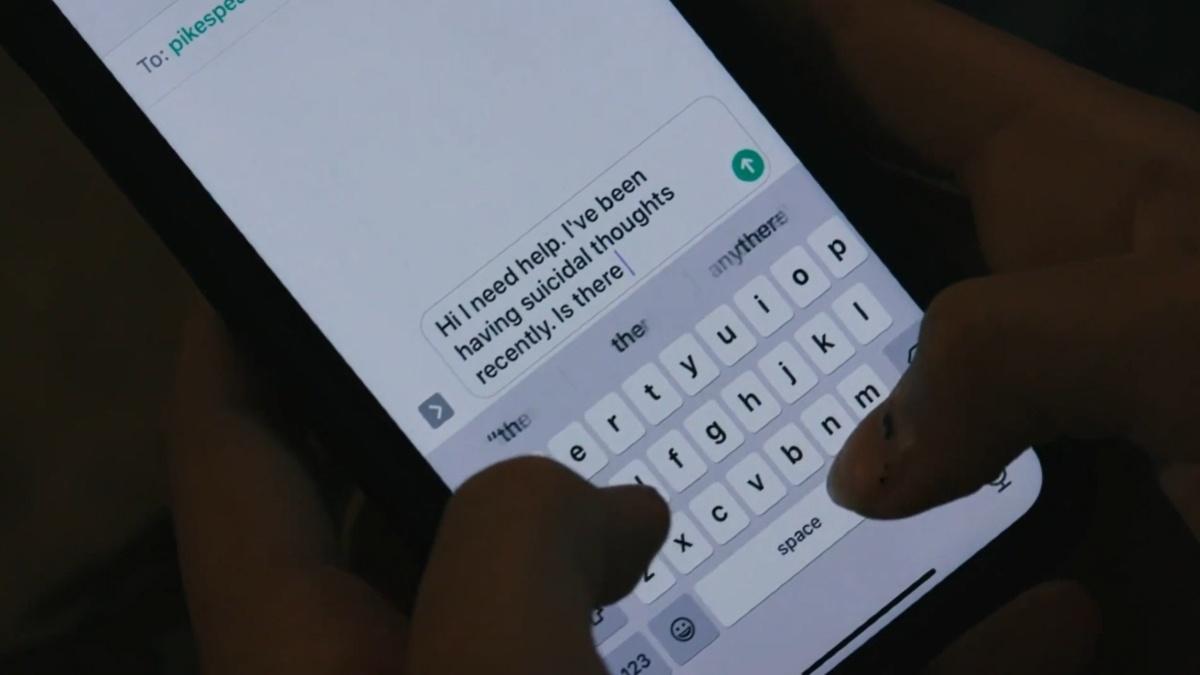

If you have an immediate mental health crisis, please call Colorado Crisis Services at 1-844-493-8255 or text TALK to 38255. Or call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. You can also chat with the Lifeline.

Gerry Lopez doesn’t really think about anything when he’s running. He likes it that way.

“Just focusing on the music and letting myself be free,” the 21-year-old says.

Growing up, many of Lopez’s peers played soccer. He preferred watching it to playing it— “Wasn't really good at it,” he explained. He only played for a sense of belonging. But during his sophomore year of high school, he quit the sport outright. One of his gym teachers recommended he try cross country or track and field instead.

Lopez says that recommendation saved his life.

Gerry's Story

Right around the time he decided to stop playing soccer, Lopez started hanging out with the “wrong crowd.” Further complicating things, he found out he would be transferring high schools, and a feeling of isolation set in.

“There was a lot of bullying, a lot of hazing that went unchecked,” he recalls. “It was one of those moments where I felt super lonely.”

One day, during math class, the school’s fire alarm went off. According to Lopez, his classmates used fire drills as a way to get outside and meet up with their friends in other classes. But Lopez didn’t have that privilege.

“I remember walking out and I just felt so alone,” Lopez says. “And I looked around and I saw so many people surrounded by at least, like, a hundred people. I just felt like I didn't belong.”

“And that was the day that I told myself that was gonna end my life.”

Lopez said the thought “terrified” him because he didn’t want to die. “I just wanted the pain to end,” he explains.

The same day of the fire drill, Lopez says he had a “what if” thought: What happens if I talk to somebody about what's going on in my head? Lopez thought about what some of his uncles taught him, that he shouldn’t be talking about his feelings. “Like, am I really going to be disowned by the men in my family?” he remembers thinking. “Am I really going to lose my manliness?”

He told himself he had two options: go speak with a professional, or go home and—as he describes it—“it’s lights out.” He decided to go speak with a counselor.

“When I was in that counselor's room, I spilled everything out,” Lopez says. “And I came home and my mom was all crying and she was telling me like, ‘Why didn't you tell me this?’”

But Lopez says one of the biggest surprises was his father’s reaction. “He was one of the guys that was raising me to be this super macho tough guy,” Lopez says. “And seeing him cry and seeing him...open up to me about all these things really gave me hope about recovery.”

A key part of that recovery process was running. “No joke. That is what kept me alive,” Lopez says. “And that slowly started to be my reason to be happy and to be alive. As much as I love running, the people that I met on the cross country team and the track team, they were my lifeline.”

Lopez is now the youth engagement coordinator for Eagle Valley Behavioral Health and a mentor with My Future Pathways, an organization that mentors mostly young men who are first generation Americans and who may face challenges in graduating high school. Lopez, who moved from Mexico to the United States with his family when he was five, can relate to these young men. He says the kids don’t understand the concept of running for fun, but he maintains that if it’s done right, running is addictive.

“We talk about resiliency, responsibility, communication skills,” Lopez says. “And they open up themselves.”

Lopez also spoke of the lack of Spanish-speaking services in his community despite the large Latinx population in Eagle County. Nearly 30% of the county is Hispanic or Latino, according to the latest census data. Part of the work Lopez does with Eagle Valley Behavioral Health is to help remedy that lack of representation and access. The organization is working to provide more services to the Hispanic/Latinx community and Lopez says he shares his story to help reduce the cultural stigma around mental health.

Lopez says the “macho mentality”--something he struggled with himself--is what prevents a lot of young men from opening up about the struggles in their life. “When it comes to your mental health, I feel like there's no space for that [mentality], especially when things are getting really rough,” Lopez says.

Lopez has learned that he is good at “getting the best out of kids who don’t think they’re the best.” He says he’s so passionate about mentoring young men that he’d do it for free if he had to.

“Whenever they say thank you, or whenever they say I love you, or whenever they say you're like a big brother to me,” Lopez explains, “that's what drives me to keep pushing.”

"Don't Ever Give Up"

Like Lopez’s memory of the fire drill, many of the youth Rocky Mountain PBS spoke with for this project could identify a single day—if not a specific moment—where they realized they were suicidal.

For Cole, an 18-year-old in Denver, that moment was a bus ride home.

Cole's Story

“I don’t remember what the details of that day were like. I just hopped on the bus and I think I had a nervous breakdown, so I got off the bus, and I was going to walk into a busy street and just let a car hit me,” Cole recalled. “That’s how it all started, I guess. From not wanting to live actively wanting to die.”

Thankfully, Cole never walked into that street. He waited for his mother to pick him up and, as he remembers it, “told her everything.”

For a while, Cole was confused as to why he was having these suicidal thoughts.

“I’ve come to the conclusion that I just wanted the pain to stop,” he explains. “I just wanted to be happy. If I had died, then I assumed that I wouldn’t feel anything, and so if I didn’t feel anything, then I wouldn’t feel suffering, and therefore I’d be happy.”

Today, Cole is feeling much better than the day he got off the bus, after working on his recovery for more than a year. He has found an interest in archeology, photography, and anthropology, and recently took a trip to the plains to investigate an early 20th Century moonshining couple named the Claytons. He says he doesn’t have much advice for other young people struggling with suicidal thoughts. “All I know is that I got lucky,” he says.

But even if he doesn’t have concrete advice for others, he has found strategies that work for him.

“I constantly look for ways to get something out of everything. It’s a nice skill I’ve picked up.” In that way, he is an archeologist: constantly making discoveries in his everyday life.

Cole’s twin, Mackenzie Tucker, has also struggled with suicidal thoughts.

Mackenzie is deaf and uses Cued Speech rather than American Sign Language. She says some of her struggles with mental health when she was in high school stemmed from not having a compatible cued speech transliterator to help her understand what was going on around her in school.

Mackenzie's Story

“Being deaf can have some really big downsides,” Mackenzie explains. “It’s really hard for you to interact with other people, not because you can’t hear, but it's about the simple lack of understanding of what’s going on.”

When Mackenzie was 15, she says her grades dropped and she began losing her self-confidence. At that time, she started feeling like a “completely different person” and began thinking of suicide. She eventually told her mother, who took her to the emergency room.

“If you’re feeling suicidal, don’t keep it to yourself,” Mackenzie says. “You have to just open up and get help, and don’t ever give up.”

Mackenzie has now found a passion in writing, and one day hopes to travel the world and become a speaker and an author. “I just want to make things better for the world and enjoy myself too,” she says.

We spoke with Cole and Mackenzie’s mother, Lisa Weiss, about what it was like raising twins who both struggled with suicidal thoughts.

“I've experienced a lot of hard things in my life and I've certainly experienced a lot of hard things as a mother, but having kids who are suicidal... it's the worst thing that I've ever had to deal with,” she said.

Sharing Her Story

Like Mackenzie and her writing, Deven Quintanilla discovered TikTok as a way to express herself in ways she couldn’t before.

“It sounds kind of weird, but putting on makeup when I'm sad kept me from being more sad,” says Deven, an 18-year-old from Colorado Springs who is studying to become an esthetician. “I got up and I did something and I couldn't cry cause I had makeup on. So it kind of made everything better.”

Deven says when she is putting on makeup—be it on herself or her family and friends—she feels like how a painter must feel when working on their masterpiece. Her makeup skills are apparent in her videos on TikTok, the video-sharing social media platform where Deven has over 19,000 followers. Deven, who graduated from Pine Creek High School, says she was initially drawn to TikTok as a replacement for Vine—a place where people could share short, funny videos.

“But now after everything that's happened in 2020,” Deven explained, “[TikTok has] become a huge platform for people to talk about politics, to talk about societal issues...their mental health recovery as well.”

Insight with John Ferrugia

Deven's Story

Young Coloradans are sharing their personal stories of crisis and recovery.

Although she frequently posts lighthearted videos of her dancing or showing off new tattoos and makeup, Deven is no stranger to talking about serious subjects in her videos.

“This is a video that doesn’t really matter how many views it gets, just as long as it touches just a couple people,” Deven says in the introduction of a video posted in late July. “From the time I was 12 to 16, I had severe depression, and I have had six suicide attempts in my life.”

In an earlier video, she compiled a photo gallery of happy memories—school dances, high school sports, graduation—with the caption “here’s all of the things I would have missed if I killed myself when I was 12 like I planned.”

Deven explained that her parents had gone through a “really nasty divorce.” While she understands it’s common for young people to feel sad when their parents separate, she said she felt “alone...worthless, hopeless.”

It reached the point where Deven was talking about taking her own life in school. “They ended up calling my mom and when she came she was with my grandmother,” Deven recalled. “We all just hugged each other and broke down and cried.”

Deven was in therapy for about three years. She also credits TikTok with giving her the ability to speak candidly about her issues to people who may need help.

“It’s become a very large platform for people to spread positivity, spread help, awareness, and stuff like that,” she said about TikTok. “And sharing my story—as long as it touches one person and helps them and makes them realize that things get better—that’s all I want to do.”

Deven says she’s had people reach out to her via direct messages on social media to tell her that her videos have given them hope, and it reinforced her desire to keep making videos.

“Every day I tell them that recovery isn’t just a one-time thing. It’s an everyday thing,” Deven said. “Every day is about reminding yourself that things get better, things get easier, and there’s just things worth living for. I wouldn’t lie and say that the process is easy, but I would say it’s worth it, 100%.”

"Progress Isn't Linear"

Aimee's Story

Aimee Resnick wants other young people to know the path to recovery is not always easy.

The 15-year-old says she first planned to end her life when she was 12.

“My friend group at the time kind of dropped me and told me that I was unacceptable and unlovable in a lot of ways, and that led to me having a lot of issues around my self image and leading to just sense of overwhelm that caused me to feel numb,” Aimee explains.

Aimee’s parents found out about her plan and stopped her. One year later, Aimee says she began having issues with her identity as bisexual. She even lost a friend when she came out. And so Aimee says she attempted suicide again. This time, the police intervened.

“Personally for me, I know that when the police came to my door it was not only scary for me but also my parents,” Aimee says. “And it made me feel hesitant to reach out again to potential supports because I didn’t want the police to come to my house again.”

When she was younger, Aimee felt “unique” in her struggles with suicidal thoughts, like nobody would be able to relate to the feelings and urges she was having. She now understands this is not the case. In fact, Aimee serves on the state of Colorado’s Suicide Prevention Commission helping to lead the Youth-Specific Initiatives Workgroup.

“I realize the value of not only advocating for myself but also other people in terms of mental health,” Aimee says. “And just having an outlet for that really helped me improve.”

Her civic engagement doesn’t end there. Aimee is involved with the Colorado Youth Advisory Council (COYAC), as well as the Centennial Youth Commission, where she participates in the policy-making process of her own community.

“Even though working with all these groups helps me have an outlet to try to make things better, progress isn’t linear,” Aimee says.

“It’s not going to get better instantaneously. It’s going to take years and years of work on yourself in order to feel better. But it will happen eventually,” Aimee says. “And you’re not always going to feel that way. One day you’re just going to wake up and you’ll realize that you’re doing better than you were two months ago, or two years ago.”

More from Lifelines: Preventing Youth Suicide

This story is part of a collaboration with FRONTLINE, the PBS series, through its Local Journalism Initiative, which is funded by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Spotlight Newsletter

Community stories from across Colorado and updates on your favorite PBS programs, in your inbox every Tuesday.